Hepatitis Testing - CAM 127

Description

Infectious hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis viruses. Hepatitis C is a bloodborne virus that can be spread via sharing needles or other equipment to inject drugs as well as in inadequate infection control in healthcare settings.1 Hepatitis C causes liver disease and inflammation. A chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can lead to hepatic damage, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and is the most common cause of liver transplantation in the United States.2

Hepatitis B is spread by the “Percutaneous, mucosal, or nonintact skin exposure to infectious blood, semen, and other body fluids.” As the hepatitis B virus is concentrated most highly in blood, “percutaneous exposure is an efficient mode of transmission,” though hepatitis B virus (HBV) can also be transmitted through birth to an infected mother and sexual contact with an infected person and less commonly through needle sticks or other sharp instrument injuries, organ transplantation and dialysis, and interpersonal contact through sharing items, such as razors or toothbrushes or contact with open sores of an infected person. Similar to HCV infection, 15% to 25% of people with chronic HBV infection develop chronic liver disease.3

The general route of transmission for the hepatitis A virus (HAV) is through the fecal-oral route by close person-to-person contact with an infected person, sexual contact with an infected person, or the ingestion of contaminated food or water, with the bloodborne transmission of HAV being uncommon.3 Though death is uncommon and most people with acute HAV infection recover with no lasting liver damage, HAV remains a worldwide public health issue and is endemic in many low- to middle-income countries.3,4

Terms such as male and female are used when necessary to refer to sex assigned at birth.

For HCV and HBV screening in pregnant individuals, please see AHS-G2035-Prenatal Screening (Nongenetic).

Regulatory Status

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Many labs have developed specific tests that they must validate and perform in house. These laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) are regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA ’88). LDTs are not approved or cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

Policy

Application of coverage criteria is dependent upon an individual’s benefit coverage at the time of the request.

Hepatitis B

- For all individuals 18 years of age and older, triple panel testing (hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg], hepatitis B surface antibody [anti-HBs], total antibody to hepatitis B core antigen [anti-HBc]) for Hepatitis B (HBV) infection once per lifetime is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For asymptomatic, non-pregnant individuals, the following annual HBV infection screening is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- HBsAg and hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) for infants born from an HBsAg-positive individual.

- Triple panel testing (HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc) when one of the following high-risk situations is met:

- For individuals born in or who have recently traveled to geographic regions with a HBV prevalence 2% or higher (see Note 1).

- For U.S.-born individuals not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in geographic regions with an HBV prevalence 8% or higher (see Note 1).

- For individuals with a history of incarceration.

- For individuals infected with HIV.

- For individuals with a history of sexually transmitted infections or multiple sex partners.

- For men who have sex with men.

- For household contacts, needle-sharing contacts, and sex partners of HBV-infected individuals.

- For injection-drug users.

- For individuals with an active hepatitis C virus infection or who have a history of hepatitis C virus infection.

- For individuals with elevated liver enzymes.

- For individuals who are on long-term hemodialysis treatment.

- For individuals with diabetes.

- For healthcare and public safety workers exposed to blood or body fluids.

- For individuals who are receiving immunosuppressant therapy.

- For individuals who test positive for anti-HBc, follow up IgM antibody to anti-HBc (IgM anti-HBc) testing to distinguish between an acute or chronic infection is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For the confirmation of seroconversion after hepatitis B vaccination, anti-HBs testing is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals who test positive for HBV by initial antibody screening and who will undergo immunosuppressive drug therapy, HBV DNA testing is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

Hepatitis C

- For all individuals 18 years of age and older, antibody testing for Hepatitis C (HCV) infection once per lifetime is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For any individual with the following recognized conditions or exposures, one-time, post-exposure antibody testing for HCV infection is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- For individuals who have used illicit intranasal or injectable drugs.

- For individuals who have received clotting factor concentrates produced before 1987.

- For individuals with a history of hemodialysis.

- For individuals with evidence of liver disease (based on clinical presentation, persistently abnormal ALT levels, or abnormal liver function studies).

- For individuals infected with HIV.

- For individuals who received an organ transplant before July 1992.

- For individuals who received a blood transfusion or blood component before July 1992.

- For individuals notified that they received blood from a donor who later tested positive for an HCV infection.

- For individuals with a history of incarceration.

- For individuals who received a tattoo in an unregulated setting.

- For healthcare, emergency medical, and public safety workers after needle sticks, sharps, or mucosal exposures to HCV-positive blood.

- For children born from an HCV-positive individual.

- For current sexual partners of HCV-infected persons.

- Antibody testing for HCV once every three months is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY for individuals with any of the following ongoing risk factors (while risk factors persist):

- For individuals who currently inject drugs and share needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment.

- For individuals who are receiving ongoing hemodialysis.

- For individuals engaging in high-risk sexual behavior.

- Qualitative nucleic acid testing for HCV is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY in any of the following situations:

- As a follow up for individuals who test positive for HCV by initial antibody screening (to differentiate between active infection and resolved infection).

- One time screening for perinatally exposed infants who are 2-6 months of age.

- For individuals who are immunocompromised.

- Prior to the initiation of direct acting anti-viral (DAA) treatment, one time testing for HCV genotype to guide selection of the most appropriate antiviral regimen is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- Testing for HCV viral load with a quantitative nucleic acid test is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY in any of the following situations:

- Prior to the initiation of DAA therapy.

- After four weeks of DAA therapy.

- At the end of treatment.

- Twelve, twenty-four, and forty-eight weeks after completion of treatment.

Hepatitis A

- For individuals with signs and symptoms of acute viral hepatitis and who have tested negative for HBV and HCV, testing for IgM anti-hepatitis A (HAV) or qualitative testing for HAV RNA is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- Quantitative nucleic acid testing for HAV viral load is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

Hepatitis D

- For individuals who have tested positive for HBV, testing for hepatitis D virus (HDV) antibody (anti-HDV) or qualitative testing for HDV RNA is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- Quantitative nucleic acid testing for HDV viral load is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

NOTES:

Note 1: The CDC defines HBsAg prevalence by geographic region: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/hepatitis-b.

Table of Terminology

Rationale

Hepatitis C

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than 2.4 million people in the United States have chronic hepatitis C. The CDC reported 93,805 new cases of chronic hepatitis C and an estimated 67,400 cases of acute hepatitis C infections in 2022.5 HCV infection is the most common reason for liver transplantation in adults in the U.S. and may lead to hepatocellular carcinoma.6

It is estimated that 20% of people with HCV infection will develop cirrhosis, and nearly five percent will die from liver disease resulting from the HCV infection. The number of deaths from hepatitis is increasing and is projected to continue to increase for several more decades unless treatment is scaled up considerably.7 However, with the introduction of direct acting antiviral treatments, the rates of progression to cirrhosis and liver cancer have declined significantly, and the overall mortality related to HCV is expected to decrease.8 After infection with the hepatitis C virus, chronic infection typically develops in 50 to 85 percent of cases. Chronic HCV infection is generally slow to progress and over a period of 20 to 30 years, about five to 30 percent of those with chronic infection will develop cirrhosis.6

Hepatitis C virus is spread through exposure to blood of infected individuals. The most common way HCV exposure happens in the U.S. is through injection-drug use. Additional modes of exposure include being born to an HCV-infected individual, and through high-risk sexual behaviors, sharing personal items contaminated with infectious blood and invasive health care that involves injections. Less common risk factors include unregulated tattooing and piercing, needlestick injuries in health care settings, and, though rare in the U.S., donated blood, blood products, and organs (prior to 1992). Some countries are experiencing a recent resurgence of HCV infection among young intravenous drug users and Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals.9,10

Hepatitis C virus is a small, positive-stranded RNA-enveloped virus with a highly variable genome.11 Assessment of the HCV genotype is crucial for management of the HCV infection. There are currently six major genotypes of HCV, and major treatment decisions (regimen, dosing, duration) vary from genotype to genotype.12 Some regimens for one genotype (such as ledipasvir-sofosbuvir [“Harvoni”] for genotype one) may not be effective for another (in this case, Harvoni may be used for genotypes one, four, five, and six but not two or three).13,14

Hepatitis C virus is frequently asymptomatic, necessitating the need of strong screening procedures. As many as 50% of HCV-infected individuals are unaware of their diagnosis, and risk factors such as drug use or blood transfusions may increase risk of acquiring an HCV infection. Several expert groups, such as the CDC, have delineated screening recommendations in order to provide better care against the virus.15

Hepatitis C can be diagnosed with either serologic antibody assays or molecular RNA tests. Initial screening for HCV begins with a serologic assay, which detects the presence of HCV antibodies. This test can identify both active and resolved infections , but cannot differentiate whether the infection is acute, chronic, or no longer present.15 HCV antibodies typically become detectable four to ten weeks after exposure.16 Common serologic assays include enzyme immunoassays (EIA), chemiluminescence immunoassays (CIA), and point-of-care rapid immunoassays.15

Molecular RNA tests detect Hepatitis C RNA, and the process includes nucleic acid test (NAT) or nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). These tests can detect the virus as early as one to two weeks after initial infection and have become the gold standard for patients who have a positive EIA screening test. The NAT can detect whether a patient has a current active infection or assess response to therapy, providing either negative or positive results.16,17

In recent years, emerging viral-first testing strategies have gained attention, focusing on directly detecting HCV RNA and bypassing the need for initial antibody screening. This approach allows for earlier diagnosis and enables the identification of active infections as soon as 1-2 weeks post-exposure. These strategies are beneficial in high-risk populations, facilitating immediate care and treatment.18,19 Viral-first testing offers the opportunity to reduce delays in treatment through early detection of active HCV infections. This single-step point-of care-strategy aligns with global HCV elimination efforts through improving screening accuracy and accessibility.10

Hepatitis B

The HBV is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the hepadnavirus family. The diagnosis of its acute infection is characterized by the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), and chronic conditions develop in 90% of infants after acute infection at birth, 25%–50% of children newly infected at ages one to five years, and five percent of people newly infected as adults.3,20

Hepatitis B virus is transmitted from infected patients to those who are not immune (i.e., hepatitis B surface antibody [anti-HBs]-negative). Methods of transmission include mother-to-child (whether in utero, at birth, or after birth), breastfeeding, paternal transmission (i.e., close contact with infected blood or fluid of fathers), transfusion, sexual transmission, nosocomial infection, percutaneous inoculation, transplantation, and blood exposure via minor breaks in skin or mucous membranes.21

In the United States, an estimated 660,000 people were living with chronic hepatitis B infection in 2020, with 13,800 new infections reported in 2022.22,23 Though most people with acute disease recover with no lasting liver damage, 15% to 25% of those with chronic disease develop chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis, liver failure, or liver cancer. It is believed that there are more than 250 million HBV carriers in the world, 600,000 of whom die annually from HBV-related liver diseases. As many as 60% of HBV-infected persons are unaware of their infection, and many remain asymptomatic until the presentation of cirrhosis or late-stage liver disease.3,20,24

The initial evaluation of chronic HBV infection should include a history and physical examination focusing on “risk factors for coinfection with HCV, hepatitis delta virus (HDV), and/or HIV; use of alcohol; family history of HBV infection and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); and signs and symptoms of cirrhosis.” Furthermore, it should employ laboratory tests, such as “a complete blood count with platelets, liver chemistry tests (aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, albumin), international normalized ratio (INR), and tests for HBV replication (HBeAg), antibody to HBeAg [anti-HBe], HBV DNA,” and testing for HAV immunity with HAV immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody in those who are not immune. Other considerations include evaluation for other causes of liver disease, screening for HIV infection, screening for HCC, screening for fibrosis, and, in rare cases, a liver biopsy.20

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A infection is caused by the HAV, of which humans are the only known reservoir. The HAV virus is member of the genus Hepatovirus in the family Picornaviridae, and other previously used names for HAV infection include epidemic jaundice, acute catarrhal jaundice, and campaign jaundice.25

The HAV is generally transmitted through the fecal-oral route, either via person-to-person contact (e.g., transmission within households, within residential institutions, within daycare centers, among military personnel, or sexually) or consumption of contaminated food or water (consumption of undercooked foods or foods infected by food handlers). Additional modes of transmission include blood transfusion and illicit drug use, and it should be noted that maternal-fetal transmission has not yet been described.25

Globally, approximately 159 million new cases of HAV infection occur each year.25 However, in the United States, the successful implementation of vaccination has led to a near 90% reduction.26 In 2022, only 4,500 cases were detected.23 Acute infection by HAV is usually a self-limited disease, with fulminant manifestations of hepatic failure occurring in fewer than one percent of cases. However, symptomatic illness due to HAV still presents itself in seventy percent of infected adults. Consequently, “diagnosis of acute HAV infection should be suspected in patients with abrupt onset of prodromal symptoms (nausea, anorexia, fever, malaise, or abdominal pain) and jaundice or elevated serum aminotransferase levels, particularly in the setting of known risk factors for hepatitis A transmission” through detection of serum IgM anti-HAV antibodies due to its persistence throughout the duration of the disease.3,25

Proprietary Testing

For many years the standard approach to hepatitis diagnosis have followed a two-step testing process, beginning with antibody detection as an initial screening, followed by NAT confirming

active infection. More recently, a viral-first testing approach has emerged, prioritizing direct hepatitis viral RNA detection first. Both strategies play a critical role in hepatitis diagnostics, with serologic testing offering broad initial screening capabilities and molecular testing providing definitive identification of active infection. The choice of approach depends on factors such as test availability and patient population.

Antibody Testing

Many point-of-care tests have been developed to detect hepatitis C antibodies efficiently. These point-of-care tests are particularly important for providing care in economically impoverished areas. Examples of these tests include OraQuick, Tri-Dot and Bioline. The OraQuick HCV test is an FDA-approved point-of-care test which utilizes a fingerstick and a small whole blood sample to detect the HCV antibodies. This test is reportedly more than 98% accurate and provides results in 20 minutes.27 The fourth Generation HCV Tri-Dot is a rapid test which can detect antibody subtypes of HCV with 100% sensitivity and 98.9% specificity.28 This test uses human serum or plasma and can provide results in three minutes. Finally, the Bioline HCV is an immunochromatographic rapid test that can identify HCV antibodies in human serum, plasma, or whole blood.29 This test uses a safe fingerstick procedure to obtain a sample. Hepatitis panel tests have also been developed. For example, the VIDAS® Hepatitis panel by BioMérieux an anti-HCV test, which detects antibodies for hepatitis A, B, C, and E in less than two hours. This panel includes 11 automated assays and is a rapid, reliable and simple testing method.30

Molecular RNA Testing

Following a positive HCV antibody test, it is essential to perform a confirmatory test to detect active infection by identifying the presence of HCV RNA. Tests used for this second step of the diagnostic process include the Molbio Truenat HCV test, which uses a Chip-seq based RT-PCR quantitative approach for the diagnosis of HCV in whole blood, plasma, or serum. This test can also be used to monitor the HCV viral load in patients undergoing treatment.31 An additional test is the Abbott RealTime HCV viral load assay, which uses RT-PCR for detecting and monitoring HCV RNA in serum and plasma.32

Viral-first testing is still a new and emerging field however the leading test for this method is the Cepheid Xpert HCV test, a RT-PCR-based diagnostic tool that works from a fingerstick blood sample in a point-of-care setting. It offers rapid, accurate results in 41 minutes and has demonstrated high sensitivity (96.8%) and specificity (99.4%) in detecting active HCV infection.33,34 This test is unique in that it is not only FDA-approved but also the first HCV RNA test to become CLIA waived, allowing it to be used in diverse healthcare settings that might be easier to access for high-risk individuals.35

Vaccines

A hepatitis C vaccine is currently not available, although many vaccines are under development; barriers to the development of such a vaccine include virus diversity, a lack of knowledge of the immune responses when an infection occurs, and limited models for the testing of new vaccines.36,37 The World Health Organization hopes for a 90% reduction in new hepatitis C cases by the year 2030.37

Management of HCV infection typically involves monitoring the effect of treatment. The goal of treatment is to achieve a “sustained virologic response” (SVR), which is defined as “an undetectable RNA level 12 weeks following the completion of therapy.”38 This measure is a proxy for elimination of HCV RNA. The assessment schedule may vary regimen to regimen, but the viral load is generally evaluated every few weeks.38

Clinical Utility and Validity

In order to determine the link between hepatitis A infection and its rare complication of acute liver failure in children in Somalia, a retrospective study was conducted on children aged 0 to 18 who were admitted to the pediatric outpatient clinic and pediatric emergency departments of the Somalia Mogadishu-Turkey Training and Research Hospital, Somali, from June 2019 and December 2019, and who were tested for HAV and had complete study data available.4 The authors found that of the 219 hepatitis A cases analyzed, 25 (11%) were diagnosed with pediatric acute liver failure (PALF) while the remaining 194 were not. It was found that children with PALF had “significantly had more prolonged PT and aPPT, and higher INR values in coagulation assays; and had higher levels of albumin in biochemical tests than the group without liver failure (for all, p ≤ 0.05),” though no other significant differences were found based on the other laboratory parameters tested. Moreover, “Hepatic encephalopathy was observed in individuals with hepatitis A disease (12/219; 15.4%), in which PALF positive group (5/25;40%) was significantly higher compared to the non-PALF group (7/194; 4%) (p = < 0,001). The length of stay in the hospital or intensive care unit was significantly higher in children with acute liver failure (p = 0.001).” As such, Keles, et al. (2021) astutely notes that though “death rates of Hepatitis A infection seem to be low,” HAV infection may potentially “require long-term hospitalization of patients due to the complication of acute liver failure, which causes loss of workforce, constitutes a socio-economic burden on individuals and healthcare systems, and leads to mortality in settings where referral pediatric liver transplantation centers are not available.”4

Su, et al. (2022) evaluated the cost-effectiveness of implementing universal HBV screening in China to identify optimal screening strategies. By using a Markov cohort model, the researchers "simulated universal screening scenarios in 15 adult age groups between 18 and 70 years, with different years of screening implementation (2021, 2026, and 2031) and compared to the status quo (i.e., no universal screening),” investigating a total of 180 different scenarios. Their work found suggested that “with a willingness-to-pay level of three times the Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (US$30 828), all universal screening scenarios in 2021 were cost-effective compared with the status quo,” with the “serum HBsAg/HBsAb/HBeAg/HBeAb/HBcAb (five-test) screening strategy in people aged 18-70 years was the most cost-effective strategy in 2021” and “the two-test strategy for people aged 18-70 years became more cost-effective at lower willingness-to-pay levels.” Most importantly, they claimed that the “five-test strategy could prevent 3·46 million liver-related deaths in China over the lifetime of the cohort” and that delaying strategic intervention will reduce overall cost-effectiveness.39

Inoue, et al. (2017) described four HCV patients whose treatment failed. These four HCV patients had received a treatment regimen of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir, which is used for genotype 1b. However, these four patients were re-tested and found to have a different genotype; three patients had genotype two and the fourth patient had genotype 1a. The authors suggested that the daclatasvir plus asunaprevir regimen was ineffective for patients without genotype 1b.40

Linthicum, et al. (2016) assessed the cost-effectiveness of expanding screening and treatment coverage over a 20-year horizon. The authors investigated three scenarios, each of which expanded coverage to a different stage of fibrosis. “Net social value” was the primary outcome evaluated, and it was calculated by the “value of benefits from improved quality-adjusted survival and reduced transmission minus screening, treatment, and medical costs.” Overall, the scenario with only fibrosis stage three and fibrosis stage four covered generated $0.68 billion in social value, but the scenario with all fibrosis patients (stages zero to four) treated produced $824 billion in social value. The authors also noted that the scenario with all fibrosis stages covered created net social value by year nine whereas the scenario with only stages three and four covered needed all 20 years to break even.41

Chen, et al. (2019) completed a meta-analysis to research the relationship between type two diabetes mellitus development and patients with a HCV infection. Studies were included from 2010 to 2019. Five types of HCV individuals were incorporated in this study including those who were “non-HCV controls, HCV-cleared patients, chronic HCV patients without cirrhosis, patients with HCV cirrhosis and patients with decompensated HCV cirrhosis.”42 HCV infection was found to be a significant risk factor for type two diabetes mellitus development. Further, “HCV clearance spontaneously or through clinical treatment may immediately reduce the risk of the onset and development of T2DM [type 2 diabetes mellitus].”42

Saeed, et al. (2020) completed a systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities for patients diagnosed with a chronic hepatitis C infection. Health utility can be defined as a measure of health-related quality or general health status. A total of 51 studies comprised of 15,053 patients were included in this study. The researchers have found that “Patients receiving interferon-based treatment had lower utilities than those on interferon-free treatment (0.647 vs 0.733). Patients who achieved SVR (0.786) had higher utilities than those with mild to moderate CHC [chronic hepatitis C]. Utilities were substantially higher for patients in experimental studies compared to observational studies.”43 Overall, these results show that chronic hepatitis C infections are significantly harming global health status based on the measurements provided by health utility instruments.

Vetter, et al. (2022) conducted a retrospective study to assess the performance of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for HCV infection. Thirteen RDTs were studied including the Standard Q HCV-Ab by SD Biosensor, HCV Hepatitis Virus Antibody Test by Antron Laboratories, HCV-Ab Rapid Test by Beijing Wantal Biological Pharmacy Enterprise, Rapid Anti-HCV Test by InTec, First Response HCV Card Test by Premier Medical Corporation, Signal HCV Version 3.0 by Arkray Healthcare, TRI-DOT HCV by J. Mitra & Co, Modified HCV-only Ab Test by Biosynex SA, SD Bioline HCV by Abbott Diagnostics, OraQuick Hepatitis C virus by OraSure, Prototype HCV-Ab Test by BioLytical Laboratories, Prototype DPP HCV by Chembio Diagnostic Systems, and Prototype Care Start HCV by Access Bio. A total of 1,710 samples were evaluated in which 648 samples were HCV-positive and 264 samples were also HIV positive. In the samples from HIV negative patients, most RDTs showed high sensitivity of > 98% and specificity of >99%. In HIV positive patients, sensitivity was lower with only one RDT reaching >95%. However, specificity was higher, with only four RDTs showing a specificity of <97%. The authors concluded that these tests are compliant with the World Health Organization (WHO) guidance which recommends an HCV RDT to have a sensitivity of >98% and specificity >97%. However, in HIV positive patients, the specificity remained high, but none of the tests met the WHO sensitivity criteria. The authors conclude that "these findings serve as a valuable baseline to investigate RDT performance in prospectively collected whole blood samples in the intended use settings.”44

In a prospective study, Chevaliez, et al. (2020) evaluated the use of molecular point-of-care (POC) testing and dried blood spot (DBS) for HCV screening in people who inject drugs (PWID). A total of 89 HCV-seropositive PWID were further assessed with a liver assessment, blood tests, POC HCV RNA testing, and fingerstick DBS sampling. A total of 77 patients had paired fingerstick capillary whole blood for POC HCV RNA testing and fingerstick sampling with interpretable results, while the other 12 samples had no valid result due to low sample volume. The POC HCV RNA test detected 30 HCV-seropositive PWID and DBS sampling detected 27 HCV-seropositive PWID. The rate of invalid results using the POC test was below 10%, so it may be performed by staff without extensive clinical training in decentralizing testing location. This study also showed high concordance for detection of active HCV infection from DBS compared to the POC test. The authors conclude that the use of POC diagnostic testing and DBS sampling should be recommended as a one-step screening strategy to increase diagnosis, increase treatment, and reduce the number of visits.45

In an Australian observational study, Catlett, et al. (2021) evaluated the Aptima HCV Quant Dx Assay to see how well it could detect HCV RNA from fingerstick capillary DBS and venipuncture-collected samples. DBS collection would benefit marginalized populations in areas that may not have access to phlebotomy services or who may have difficult venous access. DBS has also been shown to “enhance HCV testing and linkage to care,” be easy for transport and storage, and can be used for other purposes like HCV sequencing and testing for HIV or hepatitis B simultaneously, which is useful in more resource-limited settings. From 164 participants, they found HCV RNA in 45 patients. The Aptima assay rendered a sensitivity and specificity of 100% from plasma, and a sensitivity of 95.6% and specificity of 94.1% from DBS. This demonstrated the comparable diagnostic performance of this assay when it comes to detecting active HCV infection from DBS samples and plasma samples, and hopefully the eventual use of other similar assays with similar performances.46

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Hepatitis C

The CDC recommends universal hepatitis C screening for

- “Hepatitis C screening at least once in a lifetime for all adults aged 18 years and older, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection (HCV RNA‑positivity) is less than 0.1%”

- “Hepatitis C screening for all pregnant individuals during each pregnancy, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection (HCV RNA‑positivity) is less than 0.1%.”47

Moreover, one-time hepatitis C testing regardless of age or setting prevalence among people with recognized conditions or exposures is recommended for the following groups:

- People who currently or have previously injected drugs and shared needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment.

- People with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- People with selected medical conditions, including people who have ever received maintenance hemodialysis and persons with persistently abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels.

- Prior recipients of transfusions or organ transplants, including:

- People who received clotting factor concentrates produced before 1987.

- People who received a transfusion of blood or blood components before July 1992.

- People who received an organ transplant before July 1992.

- People who were notified that they received blood from a donor who later tested positive for HCV infection.

- Health care, emergency medical, and public safety personnel after needle sticks, sharps, or mucosal exposures to HCV-positive blood.

- Infants born to people with known hepatitis C.”

It is also stated that “Routine periodic testing is recommended for people with ongoing risk factors (regardless of setting prevalence), including:

- People who currently inject drugs and share needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment

- People with selected medical conditions, including people who ever received maintenance hemodialysis.”

It is also recommended that “Clinicians should test anyone who requests a hepatitis C test, regardless of stated risk factors, because patients may be hesitant to share stigmatizing risks.”47

CDC screening and testing guidelines state that “Clinicians should initiate hepatitis C testing with an HCV antibody test with reflex to NAT for HCV RNA if the antibody test is positive/reactive.” Moreover, the CDC provides operational guidance for complete hepatitis C testing, noting that “It is important to reduce time to diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment initiation. CDC recommends that clinicians collect all samples needed to diagnose hepatitis C in a single visit and order HCV RNA testing automatically when the HCV antibody is reactive” and that “When the HCV antibody test is reactive, the laboratories should automatically perform NAT testing for HCV RNA detection. This automatic testing streamlines the process because it occurs without any additional action on the part of the patient or the clinician.”47

Furthermore, “HCV RNA testing is recommended for the diagnosis of current HCV infection among people who might have been exposed to HCV within the past 6 months, regardless of HCV antibody result.”

The CDC asserts that “Clinicians should use an FDA-approved HCV antibody test followed by a NAT for HCV RNA test when antibody is positive/reactive.” Such tests include

- HCV antibody test (anti-HCV) (e.g., enzyme immunoassay [EIA]).

- NAT to detect presence of HCV RNA (qualitative RNA test).

- NAT to detect levels of HCV RNA (quantitative RNA test).47

The CDC notes that “A reactive HCV antibody test result indicates a history of past or current HCV infection. A detectable HCV RNA test result indicates current infection” and urge that “NAT for detection of HCV RNA should be used among people with suspected HCV exposure within the past 6 months.”

For perinatally exposed infants, the CDC notes that “Clinicians should test all perinatally exposed infants for HCV RNA using a NAT at 2–6 months. Care for infants with detectable HCV RNA should be coordinated in consultation with a provider who has expertise in pediatric hepatitis C management. Infants with undetectable HCV RNA do not require further follow-up unless clinically warranted.”47

The CDC also notes that the initial HCV test should be “with an FDA-approved test for antibody to HCV.” A positive result for the HCV antibody indicates either a current infection or previous infection that has resolved. For those individuals, the CDC recommends testing by an FDA-approved HCV NAT to differentiate between active infection and resolved infection.10 For the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born between 1945 and 1965, the CDC states that “Persons who test anti-HCV positive or have indeterminate antibody test results who are also positive by HCV NAT should be considered to have active HCV infection; these persons need referral for further medical evaluation and care.” Finally, the CDC also recommends that repeat testing should be considered for individuals with ongoing risk behaviors.48

The CDC published guidance for healthcare personnel with potential exposure to HCV. CDC recommends testing the source patient and the healthcare personnel. When testing the source patient, baseline testing should be performed within 48 hours after exposure by testing for HCV RNA or HCV antibodies. All HCV RNA testing should be performed with a NAT. If the source patient was HCV RNA positive or if source patient testing was not performed, baseline testing for healthcare personnel should follow the same steps through NAT three to six weeks post-exposure. A final HCV antibody test should be performed at four to six months post-exposure to ensure a negative HCV RNA test result.49

No serologic marker for acute infection is available, but for chronic infections, CDC propounds the use of “Assay for anti-HCV” and “Qualitative and quantitative nucleic acid tests (NAT) to detect and quantify presence of virus (HCV RNA).”3

Following an HCV infection diagnosis the CDC recommends that clinicians should offer the following services to patients:

- “Medical evaluation (by either a primary care clinician or specialist for chronic liver disease, including treatment and monitoring).

- Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination.

- Screening and brief intervention for alcohol consumption.

- HIV risk assessment and testing.”47

Hepatitis B

The CDC offers guidance on how to make decisions on whether to test or screen for hepatitis B based on the demographic.

For adults: “CDC recommends screening all adults aged 18 and older for hepatitis B at least once in their lifetime using a triple panel test. To ensure increased access to testing, anyone who requests HBV testing should receive it regardless of disclosure of risk. Many people might be reluctant to disclose stigmatizing risks.”50

For infants: “CDC recommends testing all infants born to HBsAg-positive people for HBsAg and antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) seromarkers.”

For pregnant people: “CDC recommends HBV screening for HBsAg for all pregnant people during each pregnancy, preferably in the first trimester, regardless of vaccination status or history of testing. Pregnant people with a history of appropriately timed triple panel screening without subsequent risk for exposure to HBV (no new HBV exposures since triple panel screening) only need HBsAg screening.”50

For people at increased risk: “CDC recommends testing susceptible people periodically, regardless of age, with ongoing risk for exposures while risk for exposures persists. This includes:

- People with a history of sexually transmitted infections or multiple sex partners.

- People with history of past or current HCV infection.

- People incarcerated or formerly incarcerated in a jail, prison, or other detention setting.

- Infants born to HBsAg-positive people.

- People born in regions with HBV infection prevalence of 2% or more.

- US-born people not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in geographic regions with HBsAg prevalence of 8% or more.

- People who inject drugs or have a history of injection drug use.

- People with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

- Men who have sex with men.

- Household contacts or former household contacts of people with known HBV infection.

- People who have shared needles with or engaged in sexual contact with people with known HBV infection.

- People on maintenance dialysis, including in-center or home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

- People with elevated liver enzymes.”50

The CDC also explains that “Susceptible people include those who have never been infected with HBV and either did not complete a HepB vaccine series per ACIP recommendations or who are known to be vaccine nonresponders.”50

While previous guidance from the CDC recommended only a single HBsAg test to screen for Hepatitis B, the CDC now recommends the use of the triple panel test. “The triple panel test includes testing for:

- HBsAg

- Anti-HBs

- Total antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (total anti-HBc).”50

The CDC recommends screening for HBV in individuals receiving or needing immunosuppressive therapy. “Using the triple panel (HBsAg, anti-HBs, and total anti-HBc) is recommended for initial screening because it can help identify persons who have an active HBV infection and could be linked to care, have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (e.g., immunosuppressed persons), are susceptible and need vaccination, or are vaccinated.”51

It is noted that “When someone receives triple panel screening, any future periodic testing can use tests as appropriate (e.g., only HBsAg and anti-HBc if the patient is unvaccinated).”51

“The presence of the total anti-HBc antigen is needed to diagnose a patient with a hepatitis B infection. The results of the HBsAg, anti-HBs, and IgM anti-HBc tests indicate a patient’s type of hepatitis B and if they have developed immunity.” Following an HBV diagnosis the CDC recommends that individuals are provided with “Medical evaluation (by either a primary care clinician or specialist for chronic liver diseases) including treatment and monitoring. Supportive care for their symptoms as needed.”50

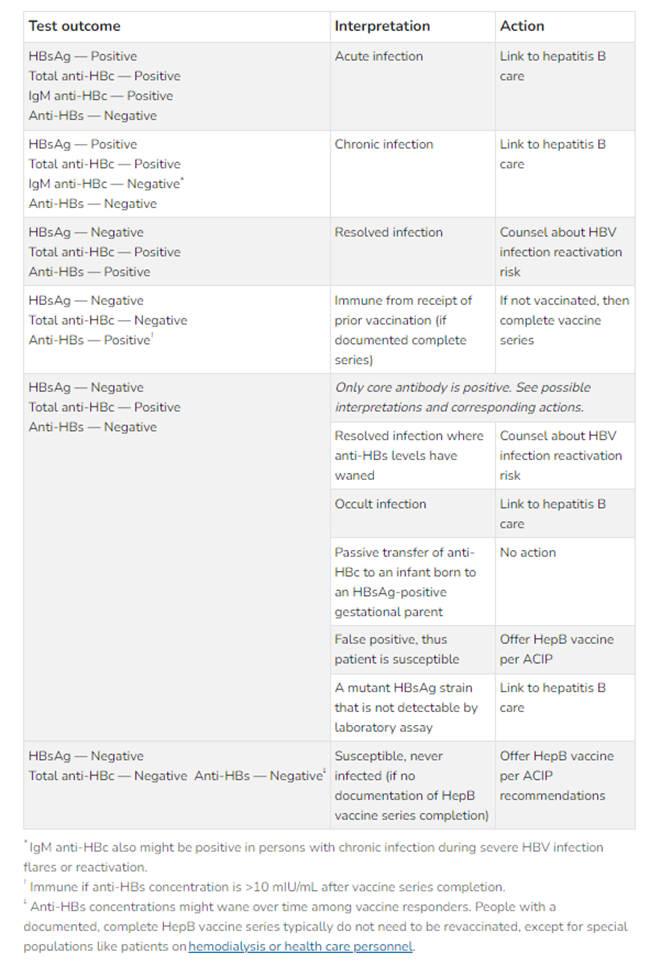

Serologic tests for chronic hepatitis B infections should include three HBV seromarkers: HBsAg, anti-HBs, and Total anti-HBc, while testing for acute infection should include HBsAg and IgM anti-HBc. The CDC provides the following chart on interpreting serologic testing results:

Figure 1: Interpreting HBV serologic test results50

For health care providers and viral hepatitis, the CDC makes the following recommendation: “For hepatitis B, CDC and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommend clinicians, other health care workers, and public safety workers with reasonably anticipated risk for exposure receive the complete hepatitis B vaccine series and have their immunity documented through post-vaccination testing.”52

Clinicians can find additional recommendations for managing HBV exposure on the CDC website, which provides an overview of various vaccination scenarios and HBsAg testing results: Responding to HBV Exposures in Health Care Settings | Hepatitis B | CDC

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A does not present as a chronic infection; as such, the CDC testing recommendations are for acute infections. The CDC lists the following clinical features when infected with HAV:

- Abdominal pain, nausea, and/or vomiting

- Dark urine or clay-colored stools

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Jaundice

- Joint pain

- Loss of appetite.53

However, it should be noted that “In children younger than 6, 70% of infections are asymptomatic. When symptoms do present, young children typically do not have jaundice, whereas most older children and adults with HAV infection have jaundice.”53

Individuals at a higher risk of HAV infection and serious disease include:

- “International travelers.

- Men who have sex with men.

- People who use or inject drugs.

- People whose jobs increase the risk of exposure.

- People who anticipate close personal contact with an international adoptee.

- People experiencing homelessness.

- Other conditions can also put people at a higher risk for developing serious disease from an HAV infection, such as chronic liver disease (including hepatitis B and hepatitis C) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).”53

Hepatitis A has an average incubation period of 28 days with a range of 15-15 days and is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route. “This can happen through:

- Close person-to-person contact with a person who is infected.

- Sexual contact with a person who is infected.

- Ingestion of contaminated food or water.

Although HAV can be detected in the blood, bloodborne transmission of HAV is uncommon.”53

The CDC cautions that “You will not be able to differentiate hepatitis A virus from other types of viral hepatitis using clinical or epidemiological features alone. Clinicians should conduct test(s) to make an accurate diagnosis.” As such, they assert that “The following are laboratory markers that, if present, indicate an acute HAV infection”

- Immunoglobulin M antibodies to HAV (IgM anti-HAV) in serum, or

- HAV RNA in serum or stool.53

The CDC notes that the presence of immunoglobulin G antibodies to HAV (IgG anti-HAV) indicates either immunity from prior infection or vaccination.

Not all tests are created equal, however; it should be mentioned that “Serologic tests for IgG anti-HAV and total anti-HAV (IgM and IgG anti-HAV combined) are not helpful in diagnosing acute illness. You should only test patients for IgM anti-HAV if they are symptomatic, and you suspect HAV infection. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin tests can aid in diagnosis.”53

“In most instances, it’s not routinely recommended to administer serologic testing for hepatitis A before vaccination. However, you may consider it in specific instances when the cost of vaccinating people who are already immune is a concern.”54

Hepatitis D

According to the CDC, “Hepatitis D is a liver infection caused by HDV. HDV is known as a ‘satellite virus’ because it can only infect people who are also infected by the HBV. HDV can cause severe symptoms and serious illness that can lead to liver damage and even death. People with hepatitis D can become infected with both HBV and HDV at the same time or get hepatitis D after first being infected with HBV.“55

Hepatitis D is uncommon in the U.S. and is spread only after coming into contact with the blood or body fluids of someone who is infected with HDV. Currently there is no vaccine for HDV, however “getting hepatitis B vaccine also protects you from hepatitis D.”55

The CDC notes the following for clinical features for HDV: “People with hepatitis D can have more severe symptoms than those who are infected with HBV alone. Symptoms usually appear 3–7 weeks after infection with HDV. They can include:

- Dark urine or clay-colored stools

- Feeling tired

- Fever

- Joint pain

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea, stomach pain, throwing up

- Yellow skin or eyes (jaundice)”55

“You may be at increased risk for hepatitis D if you are:

- Already infected with HBV.

- A person who uses or injects drugs.

- A sex partner of someone infected with HBV and HDV.

- Coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HBV.

- A man who has sex with men.

- A household contact of someone with HDV infection.

- A health care or public safety worker at risk for occupational exposure to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids.

- A hemodialysis patient.”55

A blood test is the only way to confirm HDV infection. In the 2025 case definition for HDV the CDC notes that “Identifying HDV infection is vital in the management of individuals living with HBV infection. HDV infection can accelerate progression of HBV infection, resulting in liver cirrhosis and liver failure… HDV antigen testing is not a reliable marker of current HDV infection, and HDV IgM antibody, like many IgM tests, has less than ideal specificity. For this reason, only the total anti-HDV and HDV RNA tests are included in the criteria for case classification.”56

The CDC defines HDV class classifications as ‘probable’ when the “Total antibody to hepatitis D virus (total anti-HDV) is reactive.” and ‘confirmed’ when there is “detection of HDV RNA by nucleic acid test (qualitative, quantitative, or genotype testing).”56

United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

The USPSTF recommends hepatitis C virus screening in adults aged 18 to 79 years (B recommendation) with anti-HCV antibody testing followed by confirmatory PCR testing.57

The USPSTF recommends screening for HBV infection in adolescents and adults at increased risk for infection. This applies to all asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at increased risk for HBV infection, including those who were vaccinated before being screened for HBV infection. The USPSTF defines some increased risk groups as “Persons born in the US with parents from regions with higher prevalence are also at increased risk of HBV infection during birth or early childhood, particularly if they do not receive appropriate passive and active immunoprophylaxis (and antiviral therapy for pregnant individuals with a high viral load)” and also “persons who have injected drugs in the past or currently; men who have sex with men; persons with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of persons known to be HBsAg positive.”24

The USPSTF recommends the following in relation to screening tests for HBV: “Screening for hepatitis B should be performed with HBsAg tests approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, followed by a confirmatory test for initially reactive results. A positive HBsAg result indicates chronic or acute infection. Serologic panels performed concurrently with or after HBsAg screening allow for diagnosis and to determine further management.”24

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA)

The AASLD-IDSA guidelines recommend one-time HCV testing in the following situations:

- “One-time, routine, opt out HCV testing is recommended for all individuals aged 18 years and older. Rating: I, B

- One-time HCV testing should be performed for all persons less than 18 years old with activities, exposures, or conditions or circumstances associated with an increased risk of HCV infection (see below). Rating: I, B

- Prenatal HCV testing as part of routine prenatal care is recommended with each pregnancy. Rating: I, B

- Periodic repeat HCV testing should be offered to all persons with activities, exposures, or conditions or circumstances associated with an increased risk of HCV exposure (see below). Rating: IIa, C

- Annual HCV testing is recommended for all persons who inject drugs, for HIV-infected men who have unprotected sex with men, and men who have sex with men taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Rating: IIa, C

Risk activities

- Injection-drug use (current or ever, including those who injected once)

- Intranasal illicit drug use

- Use of glass crack pipes

- Male engagement in sex with men

- Engagement in chem sex (defined as the intentional combining of sex with the use of particular nonprescription drugs in order to facilitate or enhance the sexual encounter)

Risk exposures

- Persons on long-term hemodialysis (ever)

- Persons with percutaneous/parenteral exposures in an unregulated setting

- Healthcare, emergency medical, and public safety workers after needlestick, sharps, or mucosal exposures to HCV-infected blood

- Children born to HCV-infected [individuals]

- Recipients of a prior transfusion or organ transplant, including persons who:

- Were notified that they received blood from a donor who later tested positive for HCV

- Received a transfusion of blood or blood components, or underwent an organ transplant before July 1992

- Received clotting factor concentrates produced before 1987.

- Persons who were ever incarcerated

Other considerations and circumstances

- HIV infection

- Sexually active persons about to start pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV

- Chronic liver disease and/or chronic hepatitis, including unexplained elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels.

- Solid organ donors (living and deceased) and solid organ transplant recipients.”16

Recommendations for Initial HCV Testing and Follow-up

- “HCV-antibody testing with reflex HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is recommended for initial HCV testing to establish the presence of active infection (as opposed to spontaneous or treatment-induced viral clearance). Rating: Class I, Level A

- Among persons with a negative HCV-antibody test who were exposed to HCV within the prior six months, HCV-RNA or follow-up HCV-antibody testing six months or longer after exposure is recommended. HCV-RNA testing can also be considered for immunocompromised persons. Rating: Class I, Level C

- Among persons at risk of reinfection after previous spontaneous or treatment-related viral clearance, initial HCV-RNA testing is recommended because a positive HCV-antibody test is expected. Rating: Class I, Level C

- Persons found to have a positive HCV-antibody test and negative results for HCV RNA by PCR should be informed that they do not have evidence of current (active) HCV infection but are not protected from reinfection. Rating: Class I, Level A

- Quantitative HCV-RNA testing is recommended prior to the initiation of antiviral therapy to document the baseline level of viremia (i.e., baseline viral load). Rating: Class I, Level A

- HCV genotype testing may be considered for those in whom it may alter treatment recommendations. Rating: Class I, Level A”16,58

For diagnosing and monitoring acute HCV infection, AASLD-IDSA issued the following recommendation:

- “HCV antibody and HCV RNA testing are recommended when acute HCV infection is suspected due to exposure, clinical presentation, or elevated aminotransferase levels.” (Rating: Class I, Level C)

- “After the initial diagnosis of acute HCV with viremia (defined as quantifiable RNA), HCV treatment should be initiated without awaiting spontaneous resolution.”(Rating: Class I, Level B)59

For monitoring patients who are starting hepatitis C treatment, are on treatment, or have completed therapy, AASLD-IDSA issued the following recommendations:

- “The following laboratory tests are recommended within six months prior to starting DAA (direct acting antiviral) therapy:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- International normalized ratio (INR)

- Hepatic function panel (i.e., serum albumin, total and direct bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], and alkaline phosphatase levels)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

- The following laboratory tests are recommended any time prior to starting DAA therapy:

- Quantitative HCV RNA (HCV viral load)

- If a nonpangenotypic DAA will be prescribed, then test for HCV genotype and subtype” (Rating: Class I, Level C)

- “Quantitative HCV viral load testing is recommended 12 or more weeks after completion of therapy to document sustained virologic response (SVR), which is consistent with cure of chronic infection” (Rating: Class I, Level B)60

Recommendations for Posttreatment Follow-Up for Patients in Whom Treatment Failed

- “Disease progression assessment every six to 12 months with a hepatic function panel, complete blood count (CBC), and international normalized ratio (INR) is recommended if patients are not retreated or fail a second or third DAA treatment course. (Rating: Class I, Level C)

- Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma with liver ultrasound examination, with or without alpha fetoprotein (AFP), every six months is recommended for patients with cirrhosis in accordance with the AASLD guidance on the diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Rating: Low, Conditional.”60

Recommendations for Monitoring HCV-Infected [Persons] During Pregnancy

- “As part of prenatal care, all pregnant [individuals] should be tested for HCV infection with each pregnancy, ideally at the initial visit. (Rating: I, B)

- HCV RNA and routine liver function tests are recommended at initiation of prenatal care for HCV-antibody–positive pregnant persons to assess the risk of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) and severity of liver disease. (Rating: I, B)

- All pregnant individuals with HCV infection should receive prenatal and intrapartum care that is appropriate for their individual obstetric risk(s) as there is no currently known intervention to reduce MTCT. (Rating: I, B)

- In HCV-infected pregnant individuals with pruritus or jaundice, there should be a high index of suspicion for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) with subsequent assessment of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and serum bile acids. (Rating: I, B)

- HCV-infected individuals with cirrhosis should be counseled about the increased risk of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. Antenatal and perinatal care should be coordinated with a maternal-fetal medicine (i.e., high-risk pregnancy) obstetrician (Rating: I, B).”61

Assessment of Liver Disease Severity

A section focused on determining the severity of liver diseases associated with an HCV infection is also included as part of the background of these AASLD-IDSA guidelines. The authors state the following:

“The severity of liver disease associated with chronic HCV infection is a key factor in determining the initial and follow-up evaluation of patients. Noninvasive tests using serum biomarkers, elastography, or liver imaging allow for accurate diagnosis of cirrhosis in most individuals (see pretreatment workup in When and in Whom to Initiate HCV Therapy). Liver biopsy is rarely required but may be considered if other causes of liver disease are suspected.

Noninvasive methods frequently used to estimate liver disease severity include:

- Liver-directed physical exam (normal in most patients)

- Routine blood tests (eg, ALT, AST, albumin, bilirubin, international normalized ratio [INR], and CBC with platelet count)

- Serum fibrosis marker panels

- Transient elastography

- Liver imaging (eg, ultrasound or CT scan)”16

Testing of Perinatally Exposed Children and Siblings of Children with HCV Infection

- All children born to individuals with acute or chronic hepatitis C should be tested for HCV infection.

- Antibody-based testing is recommended at or after 18 months of age. (I, A)

- Testing with an HCV-RNA assay can be considered in the first year of life, but the optimal timing of such testing is unknown. (IIa, C)

- Testing with an HCV-RNA assay can be considered as early as two months of age. (IIa, B)

- Repetitive HCV-RNA testing prior to 18 months of age is not recommended. (III, A)

- Children who are anti-HCV-positive after 18 months of age should be tested with an HCV RNA assay after age three to confirm chronic hepatitis C infection. (I, A)

- The siblings of children with vertically acquired chronic hepatitis C should be tested for HCV infection, if born from the same mother (I, C)62

Testing recommendations relating to the monitoring and medical management of children include

- “Routine liver biochemistries at initial diagnosis and at least annually thereafter are recommended to assess for HCV disease progression. (I, C)”

- “Disease severity assessment by routine laboratory testing and physical examination, as well as use of evolving noninvasive modalities (i.e., transient elastography, imaging, or serum fibrosis markers) is recommended for all children with chronic hepatitis C. (I, B).”62

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)

Hepatitis B

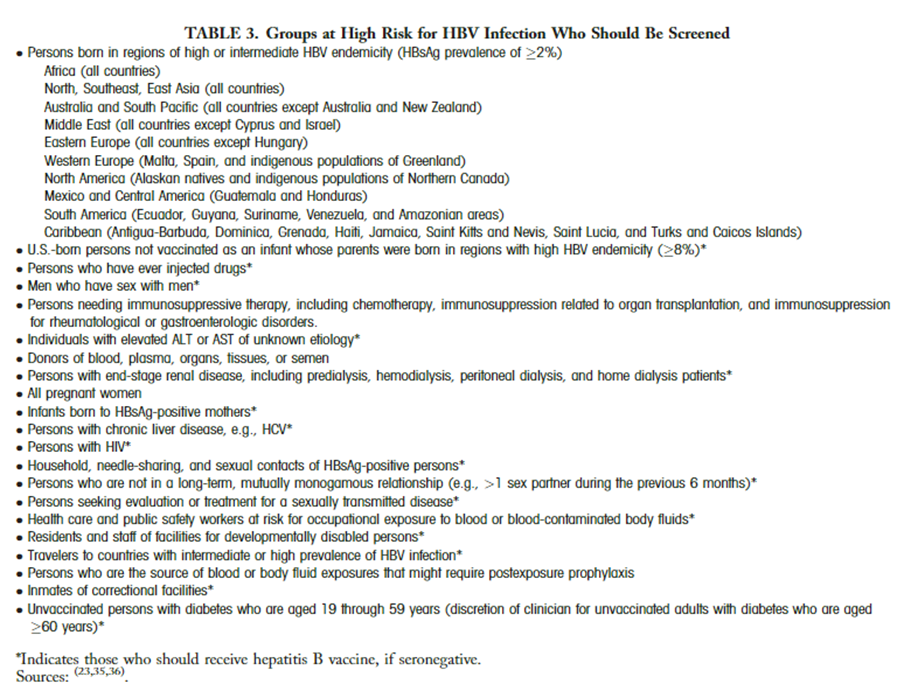

The guidance statements surrounding screening for hepatitis B infection is (shown in more detail following declare that)

- Screening should be performed using both HBsAg and anti-HBs.

- Screening is recommended in all persons born in countries with a HBsAg seroprevalence of ≥2%, U.S.-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with high HBV endemicity (≥8%), pregnant individuals, persons needing immunosuppressive therapy, and the at risk groups listed in Table 3.

- Anti-HBs–negative screened persons should be vaccinated.

- Screening for anti-HBc to determine prior exposure is not routinely recommended but is an important test in patients who have HIV infection, who are about to undergo HCV or anti-cancer and other immunosuppressive therapies or renal dialysis, and in donated blood (or, if feasible, organs).63

The AASLD recommends that the following groups are at high-risk for HBV infection and should be screened and immunized if seronegative:63

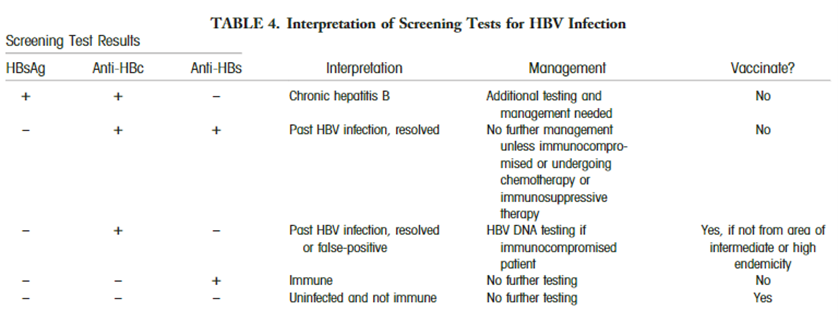

The AASLD proposes the use of various screening methods for the diagnose of hepatitis B infection: “HBsAg and antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) should be used for screening (Table 4). Alternatively, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) can be utilized for screening as long as those who test positive are further tested for both HBsAg and anti-HBs to differentiate current infection from previous HBV exposure. HBV vaccination does not lead to anti-HBc positivity.” The interpretations and follow-up steps of the screening results are summarized in their table:63

Hepatitis C

AASLD recommends not repeating hepatitis C viral load testing in patients with a previous positive (HCV) test, stating that “repeat HCV antibody testing adds cost but no clinical benefit.” They recommend “Instead, order hepatitis C viral load testing for assessment of active versus resolved infection.” This recommendation is also sponsored by the American Society for Clinical Pathology.64

World Health Organization (WHO)

Hepatitis C

The WHO recommends screening for HCV infection in a 2-step process starting with testing for antibodies and then confirming active infection through HCV RNA.

- “Testing for anti-HCV antibodies with a serological test identifies people who have been infected with the virus.

- If the test is positive for anti-HCV antibodies, a nucleic acid test for HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) is needed to confirm chronic infection and the need for treatment. This test is important because about 30% of people infected with HCV spontaneously clear the infection by a strong immune response without the need for treatment. Although no longer infected, they will still test positive for anti-HCV antibodies. This nucleic acid for HCV RNA can either be done in a lab or using a simple point-of-care machine in the clinic.

- Innovative new test such as HCV core antigen are in the diagnostic pipeline and will enable a one-step diagnosis of active hepatitis C infection in the future.”65

In a 2024 operational guide on viral hepatitis testing WHO outlines person-centered hepatitis B and C testing. The WHO have provided the following guidelines for HCV screening:

When testing among general population:

- “In settings with a ≥2% HCV antibody (anti-HCV) seroprevalence in the general population, it is recommended that all adults and adolescents have routine access to and be offered anti-HCV serological testing.

- All adults in a specific identified birth-cohort of older persons (or above a certain age) with higher HCV infection risk than the overall general population may be offered anti-HCV serological testing.”66

Routine testing among specific populations:

- “While there is no specific recommendation for HCV testing in pregnant women, it may be considered in settings of ≥2% HCV antibody seroprevalence as part of general population testing.

- In all settings screening of all blood donors for HBsAg and HCV antibodies should be mandatory.

- In all settings adults, adolescents and children with a clinical suspicion of chronic viral hepatitis (symptoms, signs, laboratory markers) should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.”66

Focused testing among most affected populations:

- “In all settings adults and adolescents from key populations (men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, trans and gender-diverse people, people in prison and other closed settings) should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- HCV antibody testing is strongly encouraged at or within one to three months of PrEP initiation (or later if not available around initiation), and every 12 months thereafter, where PrEP services are provided to populations at high risk of HCV infection.

- People at ongoing risk and a history of treatment-induced or spontaneous clearance of HCV infection may be offered 3–6 monthly testing for presence of HCV viraemia.

- Children of mothers with chronic hepatitis C (especially if HIV-coinfected) may be offered anti-HCV serological testing.

- In all settings adults and adolescents from key populations (men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, trans and gender-diverse people, people in prison and other closed settings) should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- In all settings routine serological testing for HBsAg and/or anti-HCV should be offered to indigenous populations identified as having higher HBV or HCV seroprevalence than general population.

- In all settings adults and adolescents living with HIV, TB or STIs should be offered HBsAg and HCV serological testing.

- In all settings adults and adolescents with increased HBV or HCV risks and history of health care exposure should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- In all settings adults and adolescents with increased HBV or HCV risks and history of exposure via invasive procedures outside of the health care system should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.”66

The WHO recommends facility, community, and self-testing approaches depending on when and where testing is offered as well as who is providing the services and that is what is offered. They state “Integration of HCV testing and treatment with existing care services, ideally at the same site, and decentralization to peripheral health facilities, to increase access to diagnosis, care and treatment. Task-sharing with trained non-specialist doctors and nurses to expand access to diagnosis, care and treatment. Self-testing should be offered as a testing approach in addition to existing HCV testing services.”66,67

With the goal of more efficient and simplified hepatitis diagnostics “WHO is recommending a shift to delivering testing and treatment in primary care, at harm reduction sites and in prisons, and to care delivered by general practitioners and nurses, rather than specialists.” As well “The use of point-of-care (POC) HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) assays is now recommended as an additional approach alongside laboratory-based RNA assays to diagnose the infection. This is especially applicable to marginalized populations, such as persons who inject drugs, and hard-to-reach communities with limited access to health care and high rates of loss to follow-up.”68

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B remains a significant global public health challenge despite the availability of a highly effective vaccine that provides nearly 100% protection. High-risk populations include migrants from endemic regions, household or sexual contacts of individuals with HBV infection, healthcare workers, PWID, individuals in prisons or other closed settings, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people living with HIV. The primary routes of HBV transmission include perinatal transmission from mother-to-child during birth, early childhood exposure, and contact with infected blood or bodily fluids. Transmission can also occur through unprotected sexual contact with an infected individual, unsafe injection practices, and exposure to contaminated sharp instruments.69

Hepatitis B shares clinical symptoms with hepatitis caused by other viral agents, making laboratory confirmation of HBV critical. WHO notes that “Several blood tests are available to diagnose and monitor people with hepatitis B. Some laboratory tests can be used to distinguish acute and chronic infections, whilst other can assess and monitor the severity of liver disease.” Additionally, “WHO recommends that all blood donations be tested for hepatitis B to ensure blood safety and avoid accidental transmission.”69

In a 2024 operational guide on viral hepatitis testing, WHO outlines person-centered hepatitis B and C testing. The WHO have provided the following guidelines for who qualifies for HBV screening:

Testing among general population:

- “In settings with a ≥2% HBsAg seroprevalence in the general population, it is recommended that all adults and adolescents have routine access to and be offered HBsAg serological testing”66

Routine testing among specific populations

- “All pregnant women should be tested for HIV, syphilis and HBsAg at least once and as early as possible during pregnancy.

- In all settings screening of all blood donors for HBsAg and HCV antibodies should be mandatory.

- In all settings adults, adolescents and children with a clinical suspicion of chronic viral hepatitis (symptoms, signs, laboratory markers) should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- In all settings it is recommended that HBsAg serological testing be offered and hepatitis B vaccination given to all health care workers not previously vaccinated.”66

Focused testing amount most affected populations:

- “In all settings adults and adolescents from key populations (men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, trans and gender-diverse people, people in prison and other closed settings) should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- Testing PrEP users for HBsAg once, at or within one to three months of PrEP initiation (or later if not available around initiation), is strongly encouraged, particularly in highly endemic countries.

- In all settings it is recommended that HBsAg serological testing be offered to sexual partners, children and other family members and to close household contacts of those with HBV infection.

- Infants born to mothers with presence of HBsAg should be tested for HBsAg between 6 and 12 months of age to screen for evidence of hepatitis B infection.

- In all settings adults and adolescents from key populations (men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, trans and gender-diverse people, people in prison and other closed settings) should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- In all settings routine serological testing for HBsAg and/or anti-HCV should be offered to indigenous populations identified as having higher HBV or HCV seroprevalence than general population.

- In all settings adults and adolescents living with HIV, TB or STIs should be offered HBsAg and HCV serological testing.

- In all settings adults and adolescents with increased HBV or HCV risks and history of health care exposure should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.

- In all settings adults and adolescents with increased HBV or HCV risks and history of exposure via invasive procedures outside of the health care system should be offered HBsAg and anti-HCV serological testing.”66

Recommendations for HBV DNA testing:

- “Laboratory-based HBV DNA assays: Directly following a positive HBsAg serological test result, the use of HBV DNA nucleic acid testing (NAT) (quantitative or qualitative) is recommended as the preferred strategy to assess viral load level for treatment eligibility and to monitor treatment response. (strong recommendation, moderate-certainty evidence)

- Point-of-care (POC) HBV DNA assays: POC HBV DNA nucleic acid test (NAT) assays may be used as an alternative approach to laboratory based HBV DNA testing to assess HBV DNA level for treatment eligibility and to monitor treatment response. (conditional recommendation, low-certainty evidence).”70

Recommendations for HBV DNA Reflex testing

- 'Where available, Reflex HBV DNA testing for those testing positive on HBsAg may be used as an additional strategy to promote linkage to care and treatment. This can be achieved through either laboratory-based reflex HBV DNA testing using a sample already held in the laboratory or clinic-based reflex testing in a health-care facility through immediate sample collection following a positive HBsAg rapid diagnostic test (RDT). (conditional recommendation, low-certainty evidence)”70

Hepatitis D

For the diagnosis of hepatitis D, the WHO states that HDV infection is “diagnosed by high levels of anti-HDV immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM), and confirmed by detection of HDV RNA in serum. However, HDV diagnostics are not widely available and there is no standardization for HDV RNA assays, which are used for monitoring response to antiviral therapy.”71

The WHO provides updated 2024 recommendations on HDV screening criteria and HDV diagnostic testing methods, as outlined below: Who to test for Hepatitis D infection:

- “For people with chronic hepatitis B, serological testing for anti-HDV antibodies may be performed for all individuals who are HBsAg positive. This is the preferred approach to scale up access to HDV diagnosis and linkage to care.

- In settings in which a universal anti-HDV antibody testing approach is not feasible because laboratory capacity or other resources are limited, testing for anti-HDV may be given priority in specific populations of HBsAg-positive individuals, including the following:

- people born in HDV-endemic countries, regions and areas;

- people with advanced liver disease;

- those receiving HBV treatment and those with features suggesting HDV infection (such as low HBV DNA with high alanine transaminase (ALT) levels); and

- people considered to have increased risk of HDV infection, including haemodialysis recipients, people living with hepatitis C or HIV, people who inject drugs, sex workers and men who have sex with men.”66

How to test for HDV infection: testing strategy and choice of serological and NAT assays:

- “People with CHB (HBsAg positive) may be diagnosed with hepatitis D by using a serological assay to detect total anti-HDV followed by an NAT to detect HDV RNA and active (viraemic) infection among those who are anti-HDV positive. Assays should meet minimum quality, safety and performance standards. (conditional recommendation, low- certainty evidence)

- Reflex testing for anti-HDV antibody testing following a positive HBsAg test result and also for HDV RNA testing (where available) following a positive anti-HDV antibody test result, may be used as an additional strategy to promote diagnosis. (conditional recommendation, low-certainty evidence)”70

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A associated with unsafe water or food, inadequate sanitation, poor personal hygiene and oral-anal sex. While there is a vaccine for HAV the WHO notes that “hepatitis A virus is transmitted primarily by the faecal-oral route; that is when an uninfected person ingests food or water that has been contaminated with the faeces of an infected person.”72

American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)

Hepatitis B

“The AGA recommends screening for HBV (HBsAg and anti-HBc, followed by a sensitive HBV DNA test if positive) in patients at moderate or high risk who will undergo immunosuppressive drug therapy. (Strong recommendation; Moderate-quality evidence) The AGA suggests against routinely screening for HBV in patients who will undergo immunosuppressive drug therapy and are at low risk. (Weak recommendation; Moderate-quality evidence) Comments: Patients in populations with a baseline prevalence likely exceeding 2% for chronic HBV should be screened according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations.”73

Hepatitis B reactivation (HBVr) is the loss of immunologic suppression of HBV activity in patients who are positive for the HBV surface antigen or the HB core antibody. HBVr typically occurs alongside chronic immunosuppression; people most at risk of HBV reactivation include those with chronic HBV, prior exposure to HBV, and individuals undergoing immunosuppressive treatments such as cytotoxic chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, corticosteroids, or organ transplantation. The AG guideline on prevention and treatment of HBVr during immunosuppressive drug therapy outlined “low- (<1%), moderate (1-10%) and high (>10%) risk categories for HBVr.”74 For testing, the AGA recommends the following: “For individuals at risk of HBVr, the AGA recommends testing for hepatitis B (Strong recommendation, moderate certainty evidence).”74

Hepatitis C

The AGA released best practice statements for care of patients with chronic HCV that have achieved a SVR.

- “SVR should be confirmed by undetectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks after completion of an all-oral DAA treatment regimen.”

- “Routine confirmation of SVR at 48 weeks post end of treatment is recommended. Testing for HCV RNA at 24 weeks post treatment should be considered on an individual patient basis.”

- “Routine testing for HCV RNA beyond 48 weeks after end of treatment to evaluate for late virologic relapse is not supported by available evidence; periodic testing for HCV RNA is recommended for patients with ongoing risk factors for reinfection.”75

The AGA has also released a “pathway” for HCV treatment (an algorithm).

Prior to treatment, the AGA recommends identifying the HCV genotype, as well as taking a hepatic function panel (defined as albumin, total and direct bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase).

For all three lengths of treatment courses (8, 12, 16 weeks), the AGA recommends assessing viral load and liver function (the same hepatic panel listed above).76

European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)

Hepatitis C

The EASL released guidelines on treatment of hepatitis C. The EASL recommends:

- “Screening strategies for HCV infection should be defined according to the local epidemiology of HCV infection, ideally within the framework of local, regional or national action plans.

- Liver disease severity must be assessed prior to therapy.

- Rapid diagnostic tests using serum, plasma, fingerstick whole blood or crevicular fluid (saliva) as matrices can be used instead of classical EIAs as point-of-care tests to facilitate anti-HCV antibody screening and improve access to care.